Celebrating the witch in her truest form: a feminist icon. A brief history of witches in mythology and literature.

‘Of all things upon earth that bleed and grow,

A herb most bruised is woman.’

—Gilbert Murray, Medea of Euripides, 1912

Hags, Crones, and Enchantresses in Mythology

Discover the original stories of nine magical women as we celebrate the witch in her truest form: a feminist icon. This powerful collection of mythological writings showcases the strength and prowess of witches.

Witches in Mythology — A Modern Feminist Icon

Hag, crone, enchantress, pythoness, she-devil, sorceress—the witch has known many names. Despite not being held by binary limits, the word ‘witch’ is most often applied to women, although it has been used to condemn and condone people of all genders.

Commonly portrayed in literature as villainous or evil, the traditional idea of the witch stems from centuries-old misunderstanding and misogyny. Antagonists garbed in black shifts and tall pointy hats are featured wreaking havoc with their dark powers, often accompanied by cats and broomsticks. Yet women with magical potency have appeared in literature long before this now somewhat traditional Western image of the witch was popularised. In the stories preceding the horror of the infamous witch trials, witches were not always presented as something to fear, but as magical characters with female agency.

Early literature, myths, and folk tales from across the world tell stories of women who could harness the natural powers of the Earth, using spells and herbal potions to aid others and exact revenge. Many of these stories present witches as characters to be honoured and respected, even worshipped. From the Ancient Greek tales of Hecate and Circe to the Nordic sorceress Frejya and the Egyptian Goddess of Magic, Isis, witches in mythology are presented as women revered for their powers. Examples like this can be found woven throughout the literary history of many cultures.

Traditionally, the witch is seen as having an all-encompassing influence and control over the natural world, both mortal and immortal, and one of the arts most commonly associated with witchcraft is necromancy. Deriving from the Greek words for corpse (necro) and prophecy (mancy), necromancy is the ancient practice of communicating with spirits.

In the King James version of the Bible, the Witch of Endor is described as ‘a woman that hath a familiar spirit’ (1 Samuel 28:7) and the power to raise and summon the dead. Despite the Church’s prohibition against witchcraft or sorcery of any kind—‘Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live’ (Exodus 22:18)—Saul, a Jewish monarch of ancient Israel who appears in the Old Testament, seeks out the occult abilities of the Witch of Endor, releasing her from the threat on her life for his benefit. Some interpreters of the text teach that his later death is a punishment from God for associating with a medium.

The Witch of Endor by Elsheimer (1805)

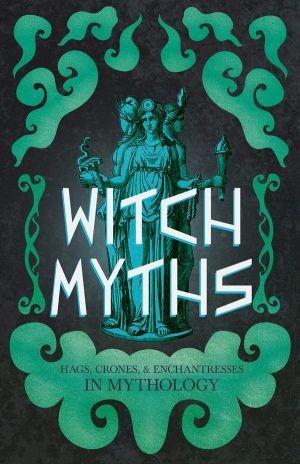

This ability to communicate with the dead is also possessed by the Egyptian Goddess Isis and the Ancient Greek witch Medea, but rather than being seen as evil or sinful practices, their craft is celebrated as a divine gift. Although the Biblical Witch of Endor uses a talisman to aid her magic, it’s Medea’s knowledge of herbs that helps her return people to life. Under the tutelage of Hecate, the Greek Goddess of Witchcraft, Medea and her aunt, Circe, learnt not only the importance of respecting and appreciating the natural power of herbs but also ‘how to render harmless and innocuous plants baleful and deadly’ (Folkard, 1884). In Greek mythology, these skilled sorceresses leveraged their knowledge of natural witchcraft for self-defence and vengeance, often against male aggressors. Circe is particularly renowned for her adept use of herbal potions, giving her the ability to transform her enemies into animals.

Circe’s Palace by L. Chalon (1899)

Similarly, such magical women are often portrayed as not only having the power to turn others into animals but also possessing their own shapeshifting capabilities, being able to adopt the guise of various beasts. Morgan le Fay, for example, a formidable enchantress from British Arthurian legend, frequently assumes the form of a bird to evade punishment for her sorcery. The Norse goddess Freyja, famed for driving a chariot drawn by black cats (a detail that suggests she’s one of the original sources for the association between witches and feline familiars) is known for her ability to transform into a falcon. Hecate, one of the most renowned witches in mythology, is a Greek goddess frequently accompanied by animals—her dogs are a sacred symbol of the Underworld and are believed to help her guard the gates of hell.

Freyja In Her Chariot from Legends of Norseland by A. Chase (1894)

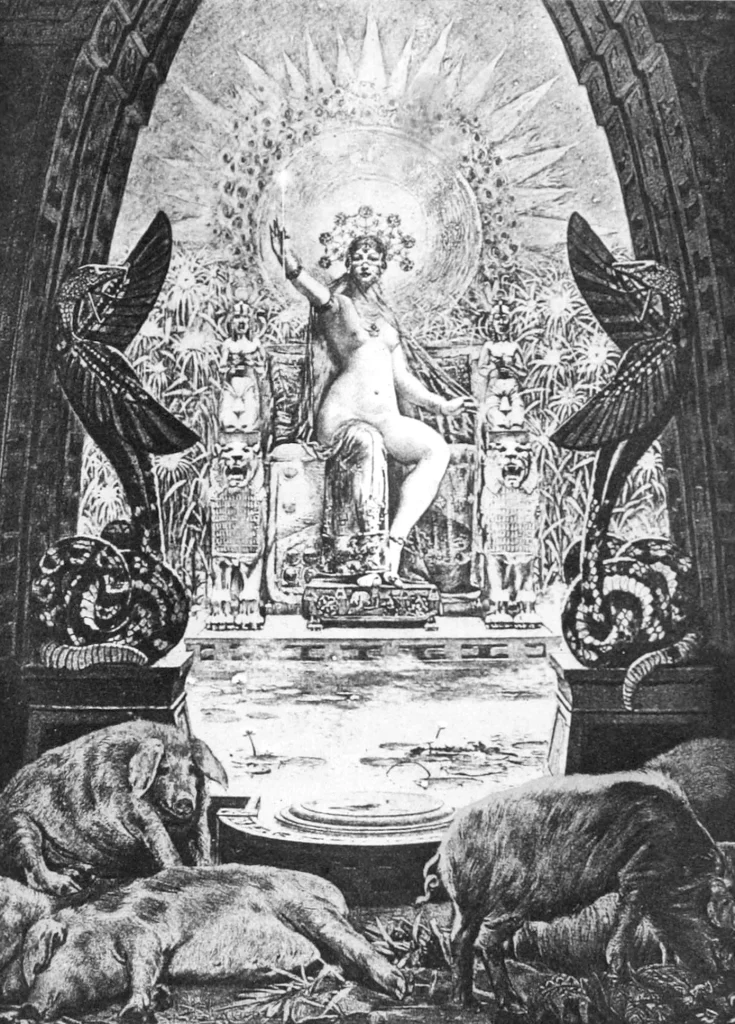

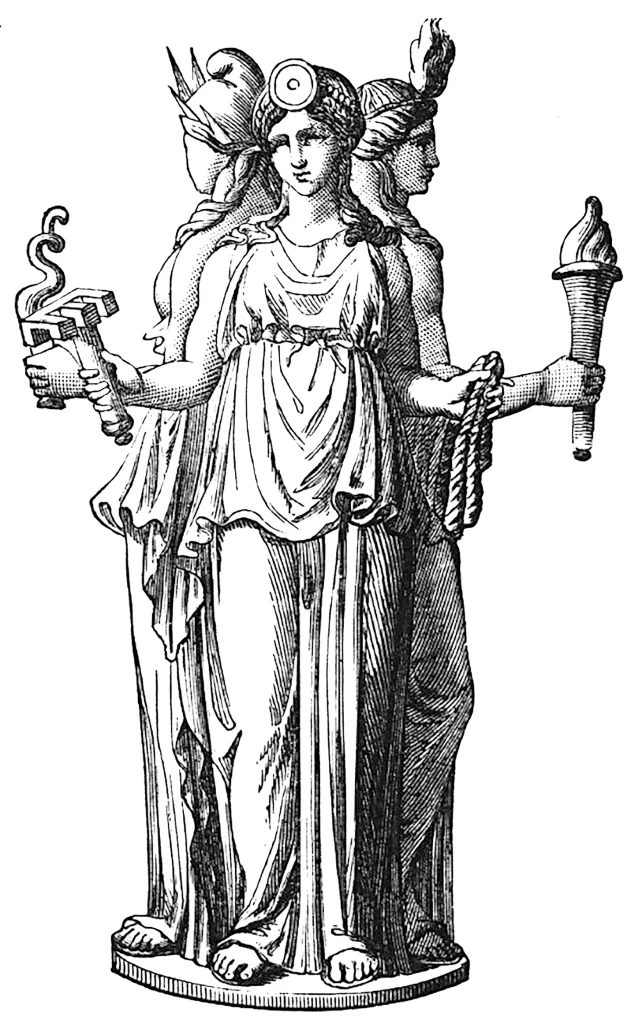

Previously mentioned as being the Goddess of Witchcraft in ancient Greek literature, Hecate is the guardian of crossroads and journeys, as well as being closely correlated with the Moon, bearing many similarities to the Roman Goddess Diana. These two witches represent the agency that underpins the female witch archetype. Both are associated with fertility and revered as protectors of mothers and childbirth. Those in labour would call upon Hecate or Diana to aid them and bring health and prosperity. This worship likely arose from the link between the Goddesses and the Moon, which follows a 28-day cycle mirrored by the average menstrual cycle, allowing women to track their progressing pregnancy by the phases of the Moon. This cyclical connection between women and the Moon emphasises their role as givers of life and the power that yields.

Three-Formed Hecate by Stéphane Mallarmé (1880)

Witches, with their ability to harness the natural magic of the world, epitomise a traditional misogynistic fear of women with faculty, establishing a character forged in the eye of discrimination. During the early modern period in Europe, witchcraft came to be seen as part of a vast, diabolical conspiracy of individuals in league with the devil, which led to large-scale witch hunts between 1500 and 1700. The terror and misinformation spread during this time have endured, tainting the way we view witches, with such negative associations materialising in our stories. The witch has come to embody a misinformed and ultimately negative archetype stemming from patriarchal values based on the idea that powerful women are something to fear, distrust, and remove. This understanding permeated the general cultural standpoint and subsequently influenced much of the media and teachings around the subject.

However, the witch’s narrative began to shift as societal understandings of women’s rights and gender equality developed. Following the third wave of feminism in the 1990s and the subsequent media produced, the witch has risen to higher popularity than ever before. Films, TV programmes, and books, such as The Craft (1996), Sabrina the Teenage Witch (1996–2003), and Harry Potter (1997–2007), were influenced by early literature’s mythological tales of witches, their powers, and their characteristics. But rather than featuring as a one-sided characterisation of evil, as seen in earlier media such as the fairy tale ‘Hansel and Gretel’ (1812) by the Brothers Grimm, these contemporary stories presented the witch as not simply ‘good’ or ‘bad’, but ordinary. Someone who bore no physical difference to the people around her while also holding no moral difference. In fact, these characters are often strong, liberated women who use their powers to help those around them, bearing far more similarity to the original witches in mythology.

As we continue to observe the impacts of the fourth wave of feminism that began in the early 2010s, an increase in mythological retellings that centre female characters, including witches, are surfacing, such as in Madelene Miller’s novel Circe (2018). Once seen as dangerous, uncanny, and other, the witch is now returning to her roots and emerging as a feminist symbol of empowerment.

In celebration of this, we’ve curated a treasury of the original witches in mythology. Witch Myths from Wyrd Books demonstrates the strength and prowess of women and their long-held tradition of wielding magic.

Hags, Crones, and Enchantresses in Mythology

Read the original stories of witches in mythology in this stunning new collection. Presenting beautiful black-and-white illustrations alongside lyrical poetry and age-old tales, Witch Myths breathes new life into the stories of magical women and resurrects the mythic witch for a modern readership.